This story is all over the Internet, even making the Guardian newspaper. I'm not entirely sure I agree with the statement that fake papers are "flooding" academia, but nonetheless it is worrying that bogus papers are being published by reputable publishers like Springer and the IEEE. However, in their defense these organisations/publishers do delegate the decisions on academic quality to individual conference chairs and programme committees. It's also not true that conferences with poor or negligible standards are just restricted to China. In 2004 I had two MSc students write and submit papers to a conference taking place in Wellington, New Zealand (KES2004). The students' work was not very good and the papers they wrote were quite unexceptional and I fully expected that they would be duly rejected. I thought the rejection would be a good learning experience for the students and may encourage them to work harder in future; both were somewhat arrogant.

I was very surprised, and slightly mortified, when both papers were accepted by the conference. My name was on these papers as co-author and knew them to be substandard. Nonetheless, I thought that attending the conference might be a good experience for the students. When they returned I was very surprised to see that the conference proceedings, published by Springer in their LNCS series, ran to two volumes of 600+ pages each. Nowhere in the proceeding's introduction did it say how many papers were submitted for review and what percentage were accepted. This conference series, run by a respected UK academic, seemed like a vanity publishing project to me.

Thursday, February 27, 2014

Monday, February 24, 2014

The IT History Society

If you have an interest in computing and its history you may be interested in joining the IT History Society, or just using its digital archives. Dedicated to preserving IT history the IT History Society (ITHS) is "an international group of over 600 members working together to document, preserve, catalog, and research the history of Information Technology (IT). Comprised of individuals, academicians, corporate archivists, curators of public institutions, and hobbyists." Its online resources include:

- A global network of IT historians and archivists

- Our exclusive International Database of Historical and Archival Sites

- IT Honor Roll of people who have made a noteworthy contribution to the industry

- IT Hardware and Companies databases

- Research links and tools to aid in the preservation of IT history

- Technology Quotes

- Calendar of upcoming events

- An active blog

- And more

Friday, February 21, 2014

Common Lisp: The Untold Story

Lisp is a remarkable programming language with a very long history; part of which is described in this republished paper published in Celebrating the 50th anniversary of Lisp, edited by Charlotte Herzeel, the conference record of Lisp50 @ OOPSLA’08 (Nashville, Tennessee, USA, 2008). That collection is available through the ACM Digital Library. If you love Lisp you'll enjoy this, and if you've never heard of Lisp you learn something - enjoy.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

Why Watson and Siri Are Not Real AI

raises the common argument that what people call AI actually isn't AI. This argument is based on John Searle's Chinese Room thought experiment in which he clearly demonstrates that computers just manipulate symbols. They do not, cannot, ane never will understand what those symbols mean. However, Alan Turing, the father of AI, never claimed that machines would understand. His test for machine intelligence, now called the Turing Test, he originally called "the imitation game." He envisaged that computers would "imitate" intelligence not be intelligent in the sense that we are. Read the Popuar Mechanics article but keep this in mind - it's ok for computers to imitate intelligence using different techiques to people just as it's ok for planes to fly without flapping their wings like birds.

Monday, February 17, 2014

This day in computing history

Thomas J. Watson Sr. was born. A shrewd businessman, Watson started his career as a cash register salesman, eventually taking the helm of IBM and directing it to world leadership in punch card equipment sales. Watson died in 1956 and control of IBM passed on to his son, Thomas Watson, Jr. brought IBM into the electronic age and, after several bold financial risks, to dominance in the computer industry.

Saturday, February 15, 2014

Turing's Halting Problem

Wired recently published an excellent article on Turing's Halting Problem (including the humorous poem SCOOPING THE LOOP SNOOPER that describes it). As Aatish Bhatia says: "Computers can drive cars, land a rover on Mars, and beat humans at Jeopardy. But do you ever wonder if there’s anything that a computer can never do?" Well there is - solve the Halting Problem.

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Facebook at 10: Zuckerberg hails 'incredible journey'

You can't have missed all the coverage of Facebook's 10th birthday in the media. If you stop and think it really is a remarkable story; from a University dorm room to a profitable global service with more 1.2 billion monthly active users. This article in The Telegraph sums it up well.

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

Computer Science in Sculpture

The Computer Science Department at the University of Auckland has three sculptures by New Zealand artist Leigh Christensen each of which has a computer science theme. Mainframe, shown on the right, is a kinetic sculpture that can add two 2 bit binary numbers to give their 3 bit sum.

The three sculptures are described in the video below, with the details of the working logic circuits of Mainframe described fully. If you are in Auckland, you're welcome to visit to view the sculptures.

The three sculptures are described in the video below, with the details of the working logic circuits of Mainframe described fully. If you are in Auckland, you're welcome to visit to view the sculptures.

Monday, February 10, 2014

After Setbacks, Online Courses Are Rethought

Tamar Lewin, of the New York Times, wrote an interesting article about MOOCS last week that seems to rather puncture the bubble that surrounds this subject. Here's Tamar's article.

Two years after a Stanford professor drew 160,000 students from around the globe to a free online course on artificial intelligence, starting what was widely viewed as a revolution in higher education, early results for such large-scale courses are disappointing, forcing a rethinking of how college instruction can best use the Internet.

A study of a million users of massive open online courses, known as MOOCs, released this month by the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education found that, on average, only about half of those who registered for a course ever viewed a lecture, and only about 4 percent completed the courses.

Much of the hope — and hype — surrounding MOOCs has focused on the promise of courses for students in poor countries with little access to higher education. But a separate survey from the University of Pennsylvania released last month found that about 80 percent of those taking the university's MOOCs had already earned a degree of some kind.

And perhaps the most publicized MOOC experiment, at San Jose State University, has turned into a flop. It was a partnership announced with great fanfare at a January news conference featuring Gov. Jerry Brown of California, a strong backer of online education. San Jose State and Udacity, a Silicon Valley company co-founded by a Stanford artificial-intelligence professor, Sebastian Thrun, would work together to offer three low-cost online introductory courses for college credit.

Mr. Thrun, who had been unhappy with the low completion rates in free MOOCs, hoped to increase them by hiring online mentors to help students stick with the classes. And the university, in the heart of Silicon Valley, hoped to show its leadership in online learning, and to reach more students.

But the pilot classes, of about 100 people each, failed. Despite access to the Udacity mentors, the online students last spring — including many from a charter high school in Oakland — did worse than those who took the classes on campus. In the algebra class, fewer than a quarter of the students — and only 12 percent of the high school students — earned a passing grade.

The program was suspended in July, and it is unclear when, if or how the program will resume. Neither the provost nor the president of San Jose State returned calls, and spokesmen said the university had no comment.

Whatever happens at San Jose, even the loudest critics of MOOCs do not expect them to fade away. More likely, they will morph into many different shapes: Already, San Jose State is getting good results using videos from edX, a nonprofit MOOC venture, to supplement some classroom sessions, and edX is producing videos to use in some high school Advanced Placement classes. And Coursera, the largest MOOC company, is experimenting with using its courses, along with a facilitator, in small discussion classes at some United States consulates.

Some MOOC pioneers are working with a different model, so-called connectivist MOOCs, which are more about the connections and communication among students than about the content delivered by a professor.

"It's like, 'The MOOC is dead, long live the MOOC,' " said Jonathan Rees, a Colorado State University-Pueblo professor who has expressed fears that the online courses would displace professors and be an excuse for cuts in funding. "At the beginning everybody talked about MOOCs being entirely online, but now we're seeing lots of things that fall in the middle, and even I see the appeal of that."

The intense publicity about MOOCs has nudged almost every university toward developing an Internet strategy.

Given that the wave of publicity about MOOCs began with Mr. Thrun's artificial-intelligence course, it is fitting that he has become emblematic of a reset in the thinking about MOOCs, after a profile in Fast Company magazine that described him as moving away from college classes in favor of vocational training in partnerships with corporations that would pay a fee.

Many educators saw the move as an admission of defeat for the idea that online courses would democratize higher education — and confirmation that, at its core, Udacity, a company funded with venture capital, was more interested in profits than in helping to educate underserved students.

"Sebastian Thrun put himself out there as a little bit of a lightning rod," said George Siemens, a MOOC pioneer who got funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for research on MOOCs, and last week convened the researchers at the University of Texas at Arlington to discuss their early results. "Whether he intended it or not, that article marks a substantial turning point in the conversation around MOOCs."

The profile quoted Mr. Thrun as saying the Udacity MOOCs were "a lousy product" and "not a good fit" for disadvantaged students, unleashing a torrent of commentary in the higher-education blogosphere.

Mr. Thrun took issue with the article, and said he had never concluded that MOOCs could not work for any particular group of students.

"I care about education for everyone, not just the elite," he said in an interview. "We want to bring high-quality education to everyone, and set up everyone for success. My commitment is unchanged."

While he said he was "super-excited" about working with corporations to improve job skills, Mr. Thrun said he was working with San Jose State to revamp the software so that future students could have more time to work through the courses.

"To all those people who declared our experiment a failure, you have to understand how innovation works," he wrote on his blog. "Few ideas work on the first try. Iteration is key to innovation. We are seeing significant improvement in learning outcomes and student engagement. "

Some draw an analogy to mobile phones, which took several generations to progress from clunky and unreliable to indispensable.

Mr. Thrun stressed that results from the second round of the San Jose experiment over the summer were much improved, with the online algebra and statistics students doing better than their on-campus counterparts. Comparisons are murky, though, since the summer classes were open to all, and half the students already had degrees.

Some San Jose professors said they found the MOOC material useful and were disappointed that the pilot was halted.

"We had great results in the summer, so I'm surprised that it's not going forward," said Julie Sliva, who taught the college algebra course. "I'm still using the Udacity videos to support another course, because they're very helpful."

Mr. Siemens said what was happening was part of a natural process. "We're moving from the hype to the implementation," he said. "It's exciting to see universities saying, 'Fine, you woke us up,' and beginning to grapple with how the Internet can change the university, how it doesn't have to be all about teaching 25 people in a room.

"Now that we have the technology to teach 100,000 students online," he said, "the next challenge will be scaling creativity, and finding a way that even in a class of 100,000, adaptive learning can give each student a personal experience."

A study of a million users of massive open online courses, known as MOOCs, released this month by the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education found that, on average, only about half of those who registered for a course ever viewed a lecture, and only about 4 percent completed the courses.

Much of the hope — and hype — surrounding MOOCs has focused on the promise of courses for students in poor countries with little access to higher education. But a separate survey from the University of Pennsylvania released last month found that about 80 percent of those taking the university's MOOCs had already earned a degree of some kind.

And perhaps the most publicized MOOC experiment, at San Jose State University, has turned into a flop. It was a partnership announced with great fanfare at a January news conference featuring Gov. Jerry Brown of California, a strong backer of online education. San Jose State and Udacity, a Silicon Valley company co-founded by a Stanford artificial-intelligence professor, Sebastian Thrun, would work together to offer three low-cost online introductory courses for college credit.

Mr. Thrun, who had been unhappy with the low completion rates in free MOOCs, hoped to increase them by hiring online mentors to help students stick with the classes. And the university, in the heart of Silicon Valley, hoped to show its leadership in online learning, and to reach more students.

But the pilot classes, of about 100 people each, failed. Despite access to the Udacity mentors, the online students last spring — including many from a charter high school in Oakland — did worse than those who took the classes on campus. In the algebra class, fewer than a quarter of the students — and only 12 percent of the high school students — earned a passing grade.

The program was suspended in July, and it is unclear when, if or how the program will resume. Neither the provost nor the president of San Jose State returned calls, and spokesmen said the university had no comment.

Whatever happens at San Jose, even the loudest critics of MOOCs do not expect them to fade away. More likely, they will morph into many different shapes: Already, San Jose State is getting good results using videos from edX, a nonprofit MOOC venture, to supplement some classroom sessions, and edX is producing videos to use in some high school Advanced Placement classes. And Coursera, the largest MOOC company, is experimenting with using its courses, along with a facilitator, in small discussion classes at some United States consulates.

Some MOOC pioneers are working with a different model, so-called connectivist MOOCs, which are more about the connections and communication among students than about the content delivered by a professor.

"It's like, 'The MOOC is dead, long live the MOOC,' " said Jonathan Rees, a Colorado State University-Pueblo professor who has expressed fears that the online courses would displace professors and be an excuse for cuts in funding. "At the beginning everybody talked about MOOCs being entirely online, but now we're seeing lots of things that fall in the middle, and even I see the appeal of that."

The intense publicity about MOOCs has nudged almost every university toward developing an Internet strategy.

Given that the wave of publicity about MOOCs began with Mr. Thrun's artificial-intelligence course, it is fitting that he has become emblematic of a reset in the thinking about MOOCs, after a profile in Fast Company magazine that described him as moving away from college classes in favor of vocational training in partnerships with corporations that would pay a fee.

Many educators saw the move as an admission of defeat for the idea that online courses would democratize higher education — and confirmation that, at its core, Udacity, a company funded with venture capital, was more interested in profits than in helping to educate underserved students.

"Sebastian Thrun put himself out there as a little bit of a lightning rod," said George Siemens, a MOOC pioneer who got funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for research on MOOCs, and last week convened the researchers at the University of Texas at Arlington to discuss their early results. "Whether he intended it or not, that article marks a substantial turning point in the conversation around MOOCs."

The profile quoted Mr. Thrun as saying the Udacity MOOCs were "a lousy product" and "not a good fit" for disadvantaged students, unleashing a torrent of commentary in the higher-education blogosphere.

Mr. Thrun took issue with the article, and said he had never concluded that MOOCs could not work for any particular group of students.

"I care about education for everyone, not just the elite," he said in an interview. "We want to bring high-quality education to everyone, and set up everyone for success. My commitment is unchanged."

While he said he was "super-excited" about working with corporations to improve job skills, Mr. Thrun said he was working with San Jose State to revamp the software so that future students could have more time to work through the courses.

"To all those people who declared our experiment a failure, you have to understand how innovation works," he wrote on his blog. "Few ideas work on the first try. Iteration is key to innovation. We are seeing significant improvement in learning outcomes and student engagement. "

Some draw an analogy to mobile phones, which took several generations to progress from clunky and unreliable to indispensable.

Mr. Thrun stressed that results from the second round of the San Jose experiment over the summer were much improved, with the online algebra and statistics students doing better than their on-campus counterparts. Comparisons are murky, though, since the summer classes were open to all, and half the students already had degrees.

Some San Jose professors said they found the MOOC material useful and were disappointed that the pilot was halted.

"We had great results in the summer, so I'm surprised that it's not going forward," said Julie Sliva, who taught the college algebra course. "I'm still using the Udacity videos to support another course, because they're very helpful."

Mr. Siemens said what was happening was part of a natural process. "We're moving from the hype to the implementation," he said. "It's exciting to see universities saying, 'Fine, you woke us up,' and beginning to grapple with how the Internet can change the university, how it doesn't have to be all about teaching 25 people in a room.

"Now that we have the technology to teach 100,000 students online," he said, "the next challenge will be scaling creativity, and finding a way that even in a class of 100,000, adaptive learning can give each student a personal experience."

Thursday, February 6, 2014

Bob Marley's birthday is a national holiday in New Zealand

|

| The Bob Marley Museum, Kingston Jamaica |

Several years ago I visited the University of the West Indies in Kingston Jamaica and went to the Bob Marley Museum in his old house in Kingston. Our guide proudly showed us the framed parliamentary legislation establishing the Bob Marley Day national holiday on Feb 6, the anniversary of Bob Marley's birth. I commented to her, "Feb 6 is a national holiday in New Zealand as well." She looked amazed and replied, "No maan, for true! Your country respect Bob that much?" I told her that "Yes, Bob Marley was very popular in New Zealand."

Of course it's a complete coincidence, Feb 6 is Waitangi Day in New Zealand that commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 between the British Crown and over 500 Māori chiefs. The treaty is considered to be New Zealand’s founding document. However, it's a very happy coincidence and there are always lots of reggae bands performing on Bob Marley's birthday on Waitangi Day.

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

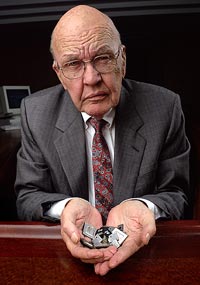

This day in history...

|

| Jack Kilby |

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

Google Acquires AI Startup DeepMind For More Than $500M

Google will buy London-based artificial intelligence company DeepMind. TechCrunch reports that the acquisition price was more than $500 million, and that Facebook was also in talks to buy the startup late last year. DeepMind has confirmed the acquisition, but hasn't disclosed the deal terms. Some pundits have said that this must be a counter to Apple's Siri, but honestly I think Google already has enough AI smarts to counter Siri. To me this look as if Google sees a could synergy between DeepMind and its own skills and wants to prevent competitors acquiring DeepMind's expertise.

Saturday, February 1, 2014

Steve Jobs Unveils Mac at Boston Computer Society, Unseen Since 1984

It’s January, 1984. Steve Jobs, nattily attired in a double-breasted suit, is demonstrating Apple’s breakthrough personal computer, Macintosh, before a packed room. He speaks alarmingly of a future controlled by IBM, and shows the famous 1984 dystopian commercial based on that theme. Jobs' presentation, at Apple’s annual shareholder meeting on January 24, is the stuff of tech-legend. But, what’s not so well remembered: is Jobs did it all twice, in less than a week. Six days after unveiling the Mac at the Flint Center near the company’s headquarters in Cupertino, Calif., he performed his show all over again to the monthly general meeting of the Boston Computer Society. His host, Jonathan Rotenberg, was a 20-year-old student at Brown University who’d co-founded the BCS in 1977 at the age of 13. You can now watch this presentation in full for the first time. It features Steve Jobs at his charismatic best; or as he might have put it "insanely great"!

You can also watch an extended version on YouTube (in 84 segments).

You can also watch an extended version on YouTube (in 84 segments).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)